The Samarco and Brumadinho tailings dam disasters in Brazil were (in no small part) the impetus for the creation of the ‘Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management’. The Standard [1] is now being rolled out around the world. It is largely a technical document, designed to achieve the ultimate goal of zero harm to people and the environment from future tailings dam failures.

However, the potential impact of the Standard might be far greater than imagined, going to the very viability of mining the critical minerals required for the energy transition in some parts of the world. The implementation of the Standard has the potential to limit the available tonnages of those critical minerals and increase the cost of producing them.

Johnson Winter Slattery’s head of Energy & Resources, Bruce Adkins shares his thoughts.

Background on tailings dams and the Samarco and Brumadinho disasters

Tailings dams are the storage facilities used to dispose of the waste rock and other materials left over after the useful minerals have been extracted at a mine site. Every mine will have tailings of some description, and so every mine requires some form of tailings storage facility. Tailings may comprise of solid and liquid waste materials and may include some elements that are toxic.

There are estimated to be many thousands of existing tailings dams at mines located all around the world.

On 5 November 2015, the Fundão tailings dam at the BHP and Vale jointly owned Samarco Mariana Mining Complex collapsed in catastrophic fashion. At the time, it was the largest ever tailings dam disaster. The death toll was 19, and the environmental damage was extensive. Mud flows covered numerous local towns, and extended all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, almost 670 kilometres away. To put it bluntly, the Samarco tailings dam failure was an environmental and humanitarian disaster.

The legal and financial fallout from the Samarco tailings dam collapse is still unfolding. BHP and Vale are facing a variety of criminal and civil lawsuits in Brazil, Australia, the US, the UK and elsewhere, which are seeking a collection of fines, penalties and other compensation.

The final total cost of the Samarco disaster might not be known for many years, but some estimates put it at US$60 billion or more. To put this in context, BHP’s total market capitalisation (as at September 2024) was US$135 billion.

Barely three years later, on 25 January 2019, the Brumadinho tailings dam at the Vale owned Córrego do Feijão mine collapsed. While the extent of the environmental impact was less than Samarco (with the damage only extending 120 kilometres downstream), the human impact was far worse, with a death toll of 272 people and thousands more injured or displaced. By any measure, Brumadinho was yet another environmental and humanitarian disaster, and the final total cost won’t be known for many years.

Live video footage of the moment the Brumadinho tailings dam collapsed can be found on YouTube. It is well worth a look. It appears as if part of a grassed mountainside suddenly collapses and turns into a raging river of destructive sludge.

While the Samarco and Brumadinho disasters were not the first tailings dam failures that the world had ever seen, they were spectacular in terms of the sheer scale of their impact, and they proved to be the impetus for change.

The ‘Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management’

The International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) shared a commitment to the adoption of global best practice on tailings storage facilities.

In the wake of the Samarco and Brumadinho disasters, the ICMM, UNEP and PRI convened a global tailings review with the aim of establishing an international standard, developed by a multi-disciplinary expert panel with inputs from a multi-stakeholder advisory group. The end result was the ‘Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management’ (Standard).

The Standard aims to prevent the catastrophic failure, and enhance the safety, of mine tailings facilities around the world. It embodies a step-change in terms of transparency and accountability, and the safeguarding of the rights of people who are affected by tailings facilities.

The primary focus of the Standard is to provide a framework that allows for safe tailings facility design, construction and management, without being overly onerous for operators and still enabling them to have a degree of flexibility.

How might this play out in practice?

While Australia, Brazil and many other countries have not (yet) made compliance with the Standard a strict legal requirement, in practice it will be a brave mining company who chooses to ignore the Standard given that it has been developed with broad international inputs and is now internationally recognised as global best practice on tailings storage facilities. If the Standard is not followed and a dam failure occurs, then this could be a ‘smoking gun’ which might have very serious ramifications for the mining company in terms of both the criminal and civil legal consequences that might flow, not to mention the reputational damage.

As a result, while not required by law, I expect that mining companies will nevertheless endeavour to comply with the Standard.

The Standard will likely impact on mining and tailings management in very different ways in different parts of the world.

A common feature of the Samarco and Brumadinho disasters was that the relevant mines and tailings dams were located in mountainous areas where space for tailings storage was limited.

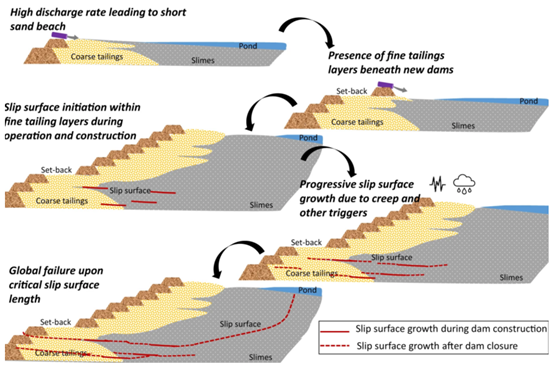

Given the difficult terrain and lack of available space, this required the construction of ‘upstream’ tailings dams. A feature of this type of facility is that a wall or bund of earth and rock is constructed, and then a layer of tailings is placed behind (i.e. upstream of) the wall. When the available space behind the wall has been filled, then another wall is built on top of the first layer, and a second layer of tailings is then deposited on top of the first layer. This process can be repeated as layer upon layer of tailings are deposited, one on top of another. This is illustrated in the image below.

From the article ‘Scientists now know how the Brumadinho dam disaster happened,

and the lessons to learn’ by Sarah Sax, 21 February 2024. Image from Zhu et al.

The problem with this type of facility is the long-term stability and integrity of the land mass created by building layer upon layer. Even without the addition of heavy rainfall or seismic movements, weaknesses in the land mass can occur, and can result in sudden and massive failures as happened at Samarco and Brumadinho. As a consequence, these ‘upstream’ tailings dams are now illegal in Brazil and Chile.

The challenge is to find an alternative to the tailings storage solutions used in the past in these mountainous mining areas of the world.

To avoid the failings of the past, future tailings storage facilities in these parts of the world will almost invariably cost more. In some cases, the terrain might be such that there is simply no safe and economic alternative, in which case the limits on tailings emplacement capacity could curtail future production levels in those areas. It is not unheard of for constraints on tailings storage capacity to act as a constraint on mine production levels. This might become much more common in the future.

Fortunately, not all mines around the world are located in difficult terrain. Here in Australia, for example, we benefit from wide open spaces and generally far more accommodating terrain for tailings storage. Upstream tailings dams, which require multiple layers upon layers, are generally not required.

While tailings facilities at Australian mines will still need to comply with the Standard, it is far less likely in Australia that compliance will add significant additional cost, or that limitations on tailings emplacement capacity will lead to the curtailment of production levels.

Final thoughts

In a world that is hungry for the minerals needed for the energy transition, compliance with the Standard could have the effect, in at least some parts of the world, of significantly increasing the cost of tailings management and therefore the cost of producing the required minerals. In some cases, limits on tailings storage capacity might also act to limit production levels.

Increased costs and constrained supply in a world of significantly increasing demand can only lead to one outcome – higher prices. And as these minerals are essential building blocks for the energy transition, this creates both risk and opportunity.

[1] The Standard was launched in 2020.